Empty corner booth in a nightclub. There are purple LED lights around the ceiling and floor.

Share

The opening paragraph, titled “Purpose,” of Minneapolis’s “Sexually Oriented Uses” ordinance reads as follows:

It is recognized that there are some uses which, because of their very nature, are recognized as having serious objectionable characteristics, thereby having a harmful effect upon the use and enjoyment of adjacent areas. Special regulation of these uses is necessary to insure that these adverse effects will not contribute to the blighting or downgrading of the surrounding neighborhood. These special regulations are included in this article. (Article IV, Chapter 549, Title 20)

Were it not for the heading, “Sexually Oriented Uses,” one might wonder what, exactly, is being discussed here. What constitutes a use that, “because of [its] very nature,” is objectionable, harmful, the antithesis of enjoyment, and, if left unchecked, could result in neighborhood ruin? It must be something powerful, dangerous, and, it seems, particularly worrisome for business and property owners.

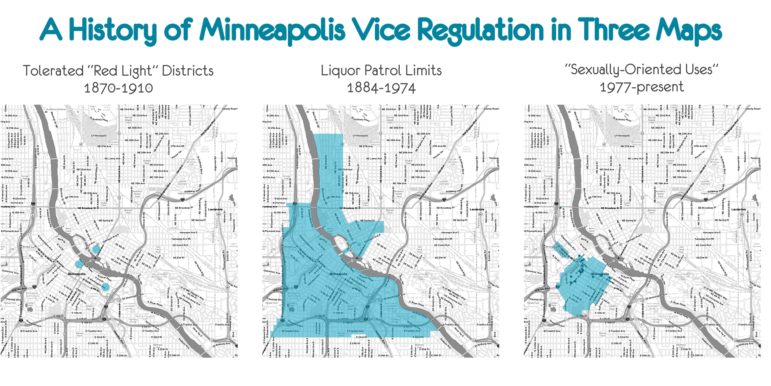

Of course, we know that the purview of the ordinance concerns sexual commerce. But it is perhaps less obvious how property values have redirected the conversation. In what follows, I offer a brief overview of the history of adult entertainment regulation in Minneapolis and zoom in on a few moments that led to the current “Sexually Oriented Use” ordinance, through which erotic dancing is regulated. By looking at City Council Proceedings and some of the ordinances that resulted from said proceedings, I hope to illuminate how erotic dance regulation has (and hasn’t) changed in Minneapolis and why worker-centered language is very much needed.[1]

Minneapolis’s Red Light Districts and an Era of Toleration[2]

As Penny Petersen details in Minneapolis Madams, the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries marked a period of time during which the City of Minneapolis tolerated sex work. Madams were allowed to own and operate brothels in designated

Because of the red light districts’ proximity to the city center and the riverfront, other kinds of entertainment cropped up nearby, including music halls, saloons, and theaters, some of which offered forms of erotic dancing like the cancan and burlesque/striptease.[6]

Minneapolis’s three

It was part of the city’s larger vision and approach to supposed “vice”—an approach that sought to control, contain, and profit from activities like drinking and erotic dancing. The

Petersen’s research shows that these years of toleration are a bit of an anomaly, and not all city council members were on board, as the votes for the monthly dispersal of funds to the Bethany Home indicate. Eventually, the naysayers won out, and by 1910 the red light districts had more or less dissolved (though sex workers continued to work in the area and elsewhere, just not with the tacit support of local government).[10] Notably, aside from the money going to the Bethany Home and a couple of ordinances related to “prostitution fines” and “public morals,” there is very little mention of sexual commerce in the council proceedings and nothing specifically pertaining to erotic dancing.

More Ordinances (and Less Tolerance)

Progressing further into the twentieth century and further away from the era of toleration, new ordinances were created that applied to a wide variety of activities, behaviors, and forms of live entertainment, including erotic dancing. In 1912, a “public morals commission” was established to deal with vice, and ordinances pertaining to “disorderly houses” and “lewdness and indecent conduct” followed in 1917 and 1919, respectively. In 1920, a zoning ordinance addressing the location and licensing of theaters entered the books, and in 1926, the city council passed an “obscene language and materials ordinance” in an attempt to control the printing, distribution, and circulation of “lewd” images and text.

Minneapolis officials also regulated erotic dancing through licensing and special permits. The city could easily revoke individual establishments’ licenses if the owners, performers, staff, or patrons did anything that could be interpreted as transgressing broadly defined and often vague laws. In 1927, for example, the Gayety Theater (a burlesque house that was located at N. 1st Ave. and Washington Ave.), had its license revoked after two city council members surveilled the theater. The subcommittee, consisting of Aldermen Johnson and Swanson, reported that they decided to visit the Gayety after hearing complaints that the performances were “indecent and immoral.” According to the council proceedings,

…it is clear [from the subcommittee’s report] that the entire show, as to dialogue and speech and the actions of persons on the stage, is highly immoral and indecent and depraved. In the audience there were a number of minors, boys and girls of the age of 17 and 18, and some apparently much younger. The attempted jokes, the dress, the conduct and the speech all flaunt questions of sex in a highly salacious and degrading manner, having a tendency to corrupt the morals of youth. (431–432, City Council Proceedings, October 14, 1927)

This approach—revoking individual venues’ licenses using catch-all obscenity ordinances—seemed to be a key way inspectors and officials dealt with erotic dancing. Coupled with the Liquor Patrol Limits, which encouraged many burlesque establishments to remain within a relatively contained area of downtown, obscenity-related licensing restrictions and revocations also helped ensure that risqué activities like burlesque didn’t spread to middle- and upper-class neighborhoods, thus safeguarding these neighborhoods and their residents from “sin” and an increasingly pressing concern: “blight.”

Cleaning Up the City

In the post-WWII era and especially in the 1960s, de-industrializing cities across the U.S. found a friend in the federal government, at least when it came to the eradication of so-called blight. This wasn’t the first clean-up attempt in Minneapolis. The difference this time, though, was money. The federal government provided the city with a $13 million grant—the nation’s largest urban renewal effort. From 1959 to 1965, the Housing and Redevelopment Authority razed nearly 200 buildings in downtown Minneapolis. Thousands of low income and poor residents were displaced, and

This new attention to blight altered the terrain for sexual commerce in significant ways. What we see at this point is a shift from religion-inflected moralizing—a save-the-sinner sort of reasoning, evident in phrases like “fallen women”—to concerns over real estate. The moralizing element never disappears, but those interested in ridding urban areas of activities that threatened Christian, middle-class sensibilities appeared to have some overlapping goals with those interested in creating a “better business climate” and increasing property values.

In addition, the 1960s ushered in significant changes in zoning and entertainment-related licensing. In 1963, the city council approved a complete overhaul of the zoning ordinance of 1924, resulting in new definitions, rules, and designated residential and commercial districts; this set the scene for the gradual corralling of adult businesses into the downtown B4 District. In 1966, the city also created A, B, and C beer and liquor license classifications that determined the kind of live entertainment that would be permitted in an establishment, should alcohol be served. The only liquor license that allowed for any kind of dancing was a Class A license. Additional classifications (D and E) would be added later.[12]

The Porn Wars

A number of sweeping ordinance changes in the 1960s thus laid the groundwork for the future development of “sexual use” categories. But other factors contributed to the creation of these categories as well. By the 1970s, sexual liberation was in full swing, and the rise of the porn industry began to occupy the attention of some radical feminists, resulting in protests and increased pressure on local governments to further restrict or even eradicate adult-oriented businesses and products altogether.[13] These “porn wars” stretched well into the 1980s and 1990s, as the possibility of privatized sexual consumption via VHS tapes came into being alongside feature-length pornographic films shown in theaters and enduring forms of live entertainment like erotic dancing.[14]

Locally, the porn wars pressure came to a head in 1983 when Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon attempted to pass an amendment to the city’s civil rights ordinance. The amendment would have defined pornography as a violation of women’s civil rights. The city council approved the ordinance in a seven-to-six vote, but it was vetoed by the mayor and never went into effect.[15]

Prior to Dworkin and MacKinnon’s arrival in Minneapolis, city officials had already been fielding calls to clamp down on and geographically contain adult businesses. This had to do, in large part, with the increased availability and accessibility of pornography. But it may have also had something to do with the abolishment, at long last, of the Liquor Patrol Limits in 1974. Now that alcohol was no longer constrained to the Gateway District, how could the city stop the spread of vice throughout the metro area? Where might erotic dance show up? An answer came in 1977 in the form of an entirely new section in the Minneapolis Code of Ordinances related to the zoning of downtown districts—Article IV: Sexually Oriented Uses.

A New Chapter?

Up until this point a patchwork of relatively imprecise, I-know-it-when-I-see it language existed in various ordinances pertaining to public morals, public dancing, liquor and entertainment, theaters, adult bookstores, saunas and massage parlors, obscene language and materials, prostitution and vagrancy, and other miscellaneous and “conditional use” categories. 1977 marks a departure from an ad hoc approach to a more purposeful grouping together of all things “adult,” with specific, very detailed definitions, location restrictions, and, significantly, plans to deal with and eventually close existing establishments that fell outside of the newly-designated downtown business area.

Forty-two years later, Article IV remains, and with a few exceptions, surprisingly little of the language has changed.[16] What has changed, though, and what zoning code sections like Article IV have helped make possible is Minneapolis’s “suburban turn,” or gentrification. As elites move back into urban areas, they bring with them suburbanized perspectives and expectations that often clash with existing adult businesses like erotic dance venues. The effects of what scholar-activist Matthew Ruben refers to as the “suburbanization of consciousness” are, indeed, tangible: with the exception of BJ’s on the corner of N. Washington Ave. and Broadway Ave., erotic dance venues located outside of the downtown B4 district have all closed.[17] And if a recent decision by the city council to deny Peter Hafiz’s petition to open a new topless club located near 3 Degrees—a nightclub-turned-church that rents space above Pizza Luce—is any indication, the gentrifying forces in Minneapolis are continuing to gather steam.[18]

Regardless of what one thinks of Peter Hafiz, the 3 Degrees Church example points to the material effects of ordinances that promote gentrification and paint erotic dancing as a dangerous activity in need of control, containment, and even eradication. Indeed, the long history of sexual use regulation in Minneapolis demonstrates a preoccupation with morality and real estate. What we haven’t seen enough of

Beth Hartman is a lecturer in the American Studies Department and the Gender, Women, and Sexuality Studies Department at the University of Minnesota. She holds a PhD in cultural anthropology from Northwestern University, and she wrote her dissertation on striptease and music, focusing primarily on the Twin Cities. She is also a musician, Feldenkrais practitioner, tour guide, and burlesque performer.

[1] From January through May of 2019, I conducted archival research at the City Clerk’s Office in City Hall in downtown Minneapolis. I perused City Council Proceedings from 1875 to 2012 and digitized/online ordinance archives from 2012 to 2019. I have not yet looked at proceedings prior to 1875, all of which are handwritten. Many thanks to Colleen Peltier and the rest of the City Clerk’s Office staff for their assistance with this project.

[2] Information in this section is largely drawn from Penny Petersen’s book, Minneapolis Madams: The Lost History of Prostitution on the Riverfront (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

[3] Petersen, Minneapolis Madams, 5–6.

[4] Heidi Heller, “Mapping Brothels” (The Historyapolis Project, 6/30/14, http://historyapolis.com/blog/ 2014/06/30/mapping-brothels/).

[5] Petersen, Minneapolis Madams, 43–51.

[6] Ibid., 66–69.

[7] Ibid., 87.

[8] The map shown includes the 1959 Liquor Patrol Limits changes, which expanded the LPL boundaries down to Franklin Ave. For more on the Liquor Patrol Limits, see Kirsten Delegard, “Map Monday: Farewell to the Patrol Limits?” (The Historyapolis Project, 11/3/14, http://historyapolis.com/blog/2014/11/03/map-monday-farewell-patrol-limits/).

[9] Petersen, Minneapolis Madams, 69–74.

[10] Ibid., 11.

[11] For more details on urban renewal in Minneapolis and St. Paul, see Judith Martin and Antony Goddard, Past Choices/ Present Landscapes: The Impact of Urban Renewal on the Twin Cities (Minneapolis: Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, 1989). For more critical, popular press perspectives on urban renewal in the Twin Cities, see, e.g., Marlys Harris, “9 worst urban planning moves in Twin Cities history” (MinnPost, 12/18/12, https://www.minnpost.com/cityscape/2012/12/9-worst-urban-planningmoves-twin-cities-history/) and Bill Lindeke, “Still Lots to Learn from Minneapolis’s Great Gateway Mistake” (

[12] The city recently did away with the A–E liquor license classification system, which was in effect through 2018. As of 2019, the entertainment classes have been reduced to “general entertainment” (all forms of legal entertainment and patron dancing), “limited entertainment” (entertainment limited to literary readings, storytelling, live solo comedians, karaoke, amplified or non-amplified music by a disc jockey or any number of musicians, and group singing by patrons of the establishment, with no patron dancing), and “no live entertainment” (no entertainment other than the use of radio, television, electronically reproduced music and jukebox). See http://www.minneapolismn.gov/licensing/alcohol/business- licensing_liquor_entertainment_classes for more information. Topless erotic dancing venues that serve alcohol must have a liquor license and appear to fall under the “general entertainment” classification. Both topless clubs and full- nudity clubs that don’t serve alcohol are also regulated through business district zoning, and they must have an existing business license of some kind (liquor license, place of entertainment license, etc.) Proposed changes, if adopted, will create additional requirements that adult entertainment establishments will have to meet in order to keep their business license. Thanks to Council Member Cam Gordon and City Attorney Joel Fussy for this information.

[13] Today, many sex-positive feminists refer to this subset of radical feminists as “Sex Work Exclusionary Radical Feminists,” or “SWERFS.”

[14] Thank you to Matthew Treon-Tchepikova and Sumanth Gopinath for this insight.

[15] For more on Minneapolis’s anti-pornography ordinance and surrounding protests, see Kirsten Delegard, “Minneapolis Anti-Pornography Ordinance” (MNOpedia, 4/7/17, http://www.mnopedia.org/thing/ minneapolis-anti-pornography-ordinance).

[16] The current ordinance may be accessed here: https://library.municode.com/mn/minneapolis/codes/ code_of_ordinances?nodeId=MICOOR_TIT20ZOCO_CH549DODI_ARTIVSEORUS

[17] For more on the “suburbanization of consciousness,” see Matthew Ruben, “Suburbanization and Urban Poverty under Neoliberalism,” in The New Poverty Studies, ed. Judith Goode and Jeff Maskovsky (New York: NYU Press, 2001): 435–469.

[18] See Susan Du, “In Minneapolis case of 3 Degrees Church vs. topless bar, religion proves victorious” (City Pages, 3/29/18, http://www.citypages.com/news/in-minneapolis-case-of-3-degreeschurch-vs-topless-bar-religion-proves-victorious/478314443).